In the fall of 1998, at seventeen years old, I started losing my eyesight from a condition known as Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (IIH). I was a teen mother with a one-year-old son, living in a transitional housing program for women who have experienced intimate partner violence. I often say that I collect exotic illnesses; this blog post will explore the rarest piece in my collection.

“An invisible disability is a superpower that can unleash the insensitive jackass from strangers in mere seconds…”

An invisible disability is a challenging physical, mental, or neurological condition that is not visible to others but has a significant impact on the person’s life. The academic in me wants to start this post off by saying something thought-provoking about the nature of invisible disabilities but, honestly, going through life with invisible limitations is just draining sometimes. It takes countless reserves of energy to educate others, advocate for yourself, and strategize how to exist in a world that either ignores your needs or does not believe you truly have them. An invisible disability is a superpower that can unleash the insensitive jackass from a stranger in mere seconds after you disclose it. Your disclosure becomes a special decoder ring, shining a light on how willfully ignorant and insensitive the world remains about able-bodied privilege.

This is what I’ve come to expect after disclosing, usually out of necessity, that I am sight-impaired. I am treated to an instant visual exam, cross-examination, and unsolicited advice, sometimes delivered in a standup comedy routine. “How many fingers do you see?”, the person will ask me as they thrust their wiggling fingers in the air. Ha, ha, ha, it’s funny cause you’re sight-impaired. I often go along with this tired bit, while wishing mild recoverable harm on these people.

Then there’s the unsolicited advice. “Have you tried vitamin B or rubbing fish eyelashes on your knee caps?” “Are you sure you can’t get your sight back?” “What about Lasik?” Navigating life with low vision fills my days with these uninvited awkward interactions, which is why I very rarely self-disclose.

I have unique visual limitations because of my diminished depth perception. This can make driving, walking in public spaces, and interacting with others challenging. Weather changes and nighttime limit my ability to drive. Entering a building can be an adventure because things disappear, reappear or remain invisible until I discover them. Cabinet doors, curbs, floor patterns, cracks in the sidewalk, and stairs can throw a wrench in my whole day. Speaking of which, I have some terrific stories about falling in public.

The Top Five Epic Falls of Colice Sanders

- When purchasing our most recent vehicle, I fell into the car dealership office, missing a singular sneaky ass step and thrusting myself into the lap of a shocked customer. My husband and mortified children later described to me how this scene had unfolded for them. They said, “It looked as if you knew the man and were trying to fight him!”.

- On a particularly snowy and icy Iowa night, in front of a Blockbuster Video (aging myself here), I slid under our parked car and I refused to get up, as I lay there laughing and peeing myself because it felt like I was reenacting a scene from the movie The Naked Gun.

- One night at college, I slid for several seconds, all the way down a lengthy hill, as if I were prepping for a sledding competition. The college library had just closed, so I had a proper audience to appreciate it and a few people may have even clapped.

- The time I fell UP the stairs, sprawled out as if I was hugging the stairs, in an overcrowded college student union, with my boss standing next to me in disbelief. He turned to me in utter confusion, with concern creasing his brows. His voice said “Are you okay”, but his eyes said, “Are you high???”.

- The time I violently face planted and fought my way into the lap of a poor spectator at a football game when I missed the riser stairs.

I can’t tell most of these stories without hysterically laughing. Falling is life for me, and if I’m the victim of anything, I am the victim of stairs. The rivalry between stairs and I goes way back. Those tricky bastards pop up and disappear at random, but I’m sure you’re wondering how we got here. How did I become vision impaired?

All Aboard The Trauma Train…

In the spring of 1996, six weeks after giving birth to my son, at sixteen years old, I was assaulted and held at knifepoint by my adopted mother/biological aunt. I left my home for good that day. I took my son and went to the only safe place I had, school. I showed up to my teen parent school with a bright red handprint on my face, ripped clothes, and knife welt marks on my neck. To better understand the relationship dynamics between my adopted mother and me, read my post What’s Left Behind: Grieving The Death Of An Estranged Abusive Parent.

This led to a summer of homelessness, placing my son in temporary foster care, and willingly checking myself into a behavior center for “troubled” teens to avoid sleeping on the streets. Eventually, I was accepted as the first teen resident in a transitional housing program for women who were displaced due to intimate partner violence. I’d been in the program for under a year when I began to lose my vision.

“I was already a fat black teen mother, what other ways did I need to stand out from my peers?”

It all started with me thinking that I needed glasses. I’d been seeing little specks float to the ground, especially when I looked at well-lit environments. I told my social worker and she took me to an eye care facility that accepted my state-funded medical insurance. I was dreading the idea of wearing glasses. I was already a fat black teen mother, what other ways did I need to stand out from my peers?

The doctor that examined my eyes seemed ok at first, but his energy seemed to change suddenly. I was new to this experience, so I wasn’t quite sure what to make of it. He kept checking and rechecking my eyes, which made me want to giggle a little. It was awkward being so close to a stranger.

We’d moved past reading letters off the wall and now he was using a fancy machine to check the pressure of my eyes, whatever that meant. It was very uncomfortable because I had to try not to blink while he wheeled what looked like a glass contact toward my right eye over and over again.

He got on the phone and called someone, then called someone else. It sounded like he was making appointments for me with several other doctors. He insisted that I be seen this week or next week at the latest.

“Suddenly, there it was radiating in his wide eyes, it was fear.”

I was not worried. I thought this must be how the process goes. When he hung up the phone, he asked to speak with my parents. I told him I only had my social worker, Doreen. He explained to her that I would need to attend several appointments over the next few weeks. All I could think about was having to miss so much school and wonder how I would get to all of those appointments. I asked him if I would be picking out my glasses today and, suddenly, there it was radiating in his wide eyes; it was fear. There was something very wrong with me, made painfully clear by the way he looked at me.

I went to the appointments over the next few weeks. Some alone by catching the city bus, some with Doreen, and some with my boyfriend. One appointment involved photographing and dilating my eyes, which was uneventful. The next appointment was for a CT and MRI scan of my head. I was terrified as I was led into the sterile room and then sealed into what I would later describe to my friends as a large and noisy coffin. Everything happened so quickly; I was afraid, I had questions, and I wanted my mom.

“I was a tragic young black welfare queen ascending to her throne of helplessness and victimhood.”

I did not know what was wrong with me. I felt invisible. I felt powerless. What were we looking for? In the eyes of some of the staff, I was a tragic young black welfare queen ascending to her throne of helplessness and victimhood.

I hadn’t learned how to recognize racism, classism, sexism, ableism, or adultism yet, but these appointments were my masterclasses in systems of oppression. Nurses, doctors, and healthcare staff did not hold back their disgust, disappointment, and disdain for me. From spontaneous lectures on the tragedy of my circumstances to blatantly ignoring my questions and concerns, I was met with so much open hostility.

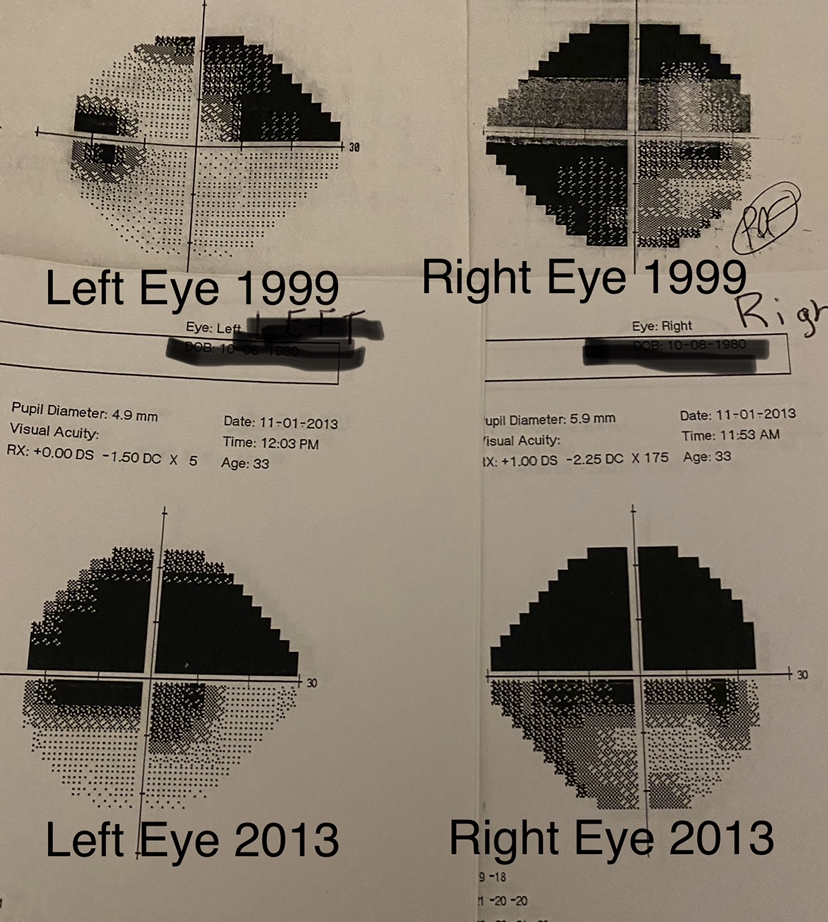

The next appointment was for completing a visual field, which is a mind-numbingly slow and tedious procedure. A visual field involves sitting in a dark room with an eye patch over one eye at a time. You face what looks like a tv satellite dish while looking for a small flash of light. You are given a clicker or item to tap on the table for each time that you see a light of varying levels and sizes flash on the dish. The process is used to assess your complete visual plane and depth perception.

“I sat there with tears sliding down my face, straining my eyes, cradling the clicker in the palm of my hand, nausea sinking into my stomach; I couldn’t see the light.”

A visual field is quiet, slow, and if you have lost as much sight as I have, it is heartbreaking. I sat there with tears sliding down my face, straining my eyes, cradling the clicker in the palm of my hand, nausea sinking into my stomach; I couldn’t see the light. The technician kept reminding me that I needed to click the clicker when I see the light, with a hint of annoyance in their voice. The lump in my throat wouldn’t let me speak up and say, “I KNOW, I CAN’T SEE!”. I was afraid that if I spoke I would start crying and not be able to stop. So I sat there and absorbed the truth, inch by inch as time crawled by. At this moment I realized what was happening to me. I was nearly blind in my right eye and my left eye was slipping too, but why?

The final appointment was a lumbar puncture. Thankfully, my boyfriend took me to this one. I didn’t know what to expect. I knew that my doctors wanted to get a read on my spinal fluid. I knew that they were concerned that I had too much. They told me how dangerous and uncomfortable the lumbar puncture could be, but that it was necessary.

I was terrified. I worked on not shaking while I undressed and put on my hospital gown. My boyfriend sat with me while I kept swiping at the tears falling down my face. I didn’t want to be paralyzed. I didn’t want to be hurt anymore. I didn’t want a room of strangers seeing my butt. I had to lay down facing a wall while the doctor and nurses were behind me. As a trauma survivor, I felt terrified about things happening to me behind my back while I lay there mostly naked… helpless.

The procedure started with a shot of a local anesthetic to numb the area around my lower spine. I am not usually bothered by needles, but this shot felt more painful than normal. The combination of the sensitivity in the area and the electric sting of the shot was too intense. The tears started again, silently; I felt so ashamed that I was crying, lying there exposed and confused.

I held still for the actual needle to enter my spine. It felt like an angry fire running through my foot and slowly moving up through every nerve of my body, I surrendered obediently to the pain. Finding complete stillness was suddenly easy, as I counted down the seconds when this would be over. The doctor’s detached voice was narrating what he was doing until suddenly he stopped talking. I felt a lukewarm liquid pool down my back. I was sure it was blood. He started stuttering. He sounded off.

With urgency in his voice, he began asking the nurse to hand him various items. Was this normal? He pulled the needle out of my spine, which caused the intense pain to happen all over again, but at least it was out now. I lay there deflated as relief and fatigue flooded my body. He told me to lie down flat and still.

“Colice, I’ve been administering lumbar punctures for over 20 years and I have never had this happen before.”

I was finally able to look at him now, his white lab coat and shirt were drenched and clinging to his chest as if someone had thrown a bucket of water on him. He looked shaken. He looked at me, deep into my eyes, and said “Colice, I’ve been administering lumbar punctures for over 20 years and I have never had this happen before”. Right then I wanted to jump out of my skin. He continued, “You have so much excess spinal fluid, that when I inserted the needle into your spinal cord, the fluid shot out through the needle and soaked my shirt.” He took off his glasses then and wiped his face, a face covered with sweat and my spinal fluid. He turned to his assistant in the room, “We have to figure out what’s going on and fast”. I lay there stunned. What the hell is spinal fluid for again? Why did I have so much of it? What did it have to do with my eyes?

In the coming weeks, I would become an expert on this condition and interacting with medical staff. I would have more lumbar punctures and eventually two major eye surgeries in a desperate attempt to salvage my rapidly declining eyesight in both eyes. I would navigate all of this mostly by myself as a seventeen-year-old girl with an 11th-grade education in progress.

“To make some sort of human connection (weather, sports, or I miss Ronald Reagan, just kidding) to remind them that I was also a person.”

This illness provided a master class in navigating a fat black female body as a welfare recipient in a middle-class world. I learned to dress up before I went to appointments. I learned to do my research and have questions beforehand and write them down. I learned to warm up the health care staff with gratitude first and then to make some sort of human connection (weather, sports, or I miss Ronald Reagan, just kidding) to remind them that while I was showing up as a fat black teen mother on welfare, I was also a person.

“WTH is Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension”

Idiopathic Intracranial hypertension or Pseudotumor Cerebri (false tumor) occurs in about 1 in 100,000 people. With this condition, a body responds as if there is a tumor by increasing spinal fluid that is collected in the head and causes sight loss or blindness. It commonly occurs in overweight women of childbearing age. This excess fluid can cause several unpleasant symptoms. Some of the symptoms are:

- Headaches

- Tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- Partial or complete blindness

- Double vision

- Blind spots

- Neck and shoulder pain

- Peripheral (side) vision loss

The medication-related treatments at the time were steroids or diuretics, lumbar punctures, weight loss, placing a shunt contraption in the spine to drain the excess fluid, or making incisions in the optic nerve to drain the fluid. My vision disappeared so quickly that I succumbed to everything but the shunt.

“Colice smash!”

I watched for over four months as my eyesight quickly disappeared before my young eyes. I had to face the very real possibility that, one day, I might not get to see my son’s face anymore. The medication was not working, I all but lost the vision in my right eye despite the surgery and my left eye was rapidly decreasing, so that left the shunt. However, when I asked for the statistical likelihood of success with a shunt because by now I had made myself an important member of my medical team, I refused to have the procedure. It had the lowest success rate at the time and a high chance of infection.

I was placed on the dangerous drug Phin-thin to promote weight loss in combination with steroids. My heart raced and I experienced these Incredible Hulk rage fits. “Colice smash!” It wasn’t just rage, sudden mood swings of tears, laughter, and sadness breezed through me daily. I eventually decided to stop taking the Phin-thin.

Taking the directions was also rough for me. My poor kidneys could barely tolerate the constant peeing. It was nearly impossible to negotiate this issue as a high schooler who needs permission to go to the bathroom. Not to mention holding my bladder during my daily two-hour bus ride to daycare and then high school, starting at 5 am and ending at 6 pm.

“I remember pointedly telling my team that if I had to drag myself across the stage on my knees, I would graduate on time with my academic honors.”

As my sight decreased, I insisted on staying in high school, even though my doctors tried to pressure me into taking time off. I remember pointedly telling my team that if I had to drag myself across the stage on my knees, I would graduate on time with my academic honors. Quitting school was not an option for me, my son’s future hung in the balance. It sounds harrowing, doesn’t it? In retrospect, honestly, it’s also very sad.

This was the beginning of a habit I’m still working to rid myself of; sacrificing my mental and physical well-being to achieve societal standards of success. I was seventeen years old and surrounded by middle-class values that encouraged me to buy into the myth of self-sufficiency, which was experiencing a rebirth in the late ’90s. I was trained to believe that people were poor because they didn’t work hard enough and that if I worked hard enough and were educated, I would be safe.

In hindsight, there are many unhealthy decisions that I made while chasing these beliefs, some of them brought me closer to my goals, some of them stole my precious time with my child and diminished my health. It wasn’t all bad. While I fought to be treated as an adult by my medical team, I also fought to have my high school experience too. I did this for my son. I knew if I didn’t soak it in and earn my high school degree, that I would not only resent him but increase our chances of remaining in poverty. This drive took me all the way into earning my Master’s degree while willfully sacrificing my mental and physical health.

Losing my sight as I was fighting to be a teenager and mother at the same time was a near-impossible battle. I had to accept that I could have gone completely blind at any point. I had to live with each day, but keep fighting for my little family. The floating specs were now heavy clouds until I lost so much sight that I couldn’t see the dark clouds anymore. It was slipping through my fingers, but thankfully I didn’t lose it all.

“It may surprise you to learn that one of the side effects that I developed was a grateful heart”

After reading about my experience with IHH, it may surprise you to learn that one of the side effects that I developed was a grateful heart. I have lived every day of my life knowing that one day I may not be able to see the beautiful faces of my loves, the beauty of sunshine sprawling onto the world around me, or the twinkling magic in a night sky. I can’t help myself in treasuring everything that I get to see each day.

I delight in seeing the lovely faces of my children as they grow into men. It’s a gift to witness the way my nieces and nephews grow and thrive in their lives, going places I’ve never been and with confidence that took me decades to build. It’s there in the faces of my friends and family as we age and learn to love ourselves a little more each year. Hell, I get teary-eyed watching the adorable neighborhood children squeal and delighting in a world of their own.

“I blow kisses as I walk away and mime you complete me to seal the deal.”

I am the mom that will ugly cry at every school play, musical, or chorus program because I am there, and I get to see it. At my children’s school functions, I’ve let the daggers bounce off me from my sons’ mortified faces as I move in close to take as many pictures as I please. I blow kisses as I walk away and mime you complete me to seal the deal.

“Even during a pandemic, as the world burns, while we’re struggling to make it through, there is still so much beauty and wonder in this world”

I’ve worked to not only fill our lives with color and beauty but also to build an appreciation for the unique ways that we show up in the world for my children. I fight back tears each time I am called to a window by one of my children to look at a sunset or a snow-covered tree. I can see it all. It is mainly from my left eye; my depth perception is nearly gone and it’s not in clear focus but DAMN IT I can see it. I get to. I almost didn’t get to. And it’s all so beautiful and wondrous and worth it. Even during a pandemic, as the world burns, while we’re struggling to make it through, there is still so much beauty and wonder in this world.

There are also still lots of stairs out there, so be careful!

You complete me.

Note: Managing your mental and physical health is a serious and important issue that should be pursued with trusted and competent healthcare professionals. I am not a healthcare professional. I am not a licensed or trained expert. I share my specific experiences and what has worked for me, in celebration of my growth and with the hope that you will find out what works for you.